Quotes from Implementing Mastery Learning by Thomas Guskey

He described studies showing that measures of students’ achievement in Grade 3 could be used to predict their achievement in Grade 11 with 80 to 90 percent accuracy. In other words, students’ achievement in early grades has a powerful deterministic effect on their achievement throughout their elementary and secondary school experiences.

Third were the results of studies showing that under one-to-one tutoring conditions, the average student learns at a level that is typically achieved by only the top 2 percent of students taught under conventional group instruction. This showed that most students are capable of exceptionally high levels of achievement. Bloom acknowledged that while mastery learning is not as effective as one-to-one tutoring, it enables a large proportion of students to learn any school subject to a very high level.

That children in the third grade are able to give such accurate estimates of their academic standing is not particularly surprising to me, and may not be to you. Despite their small size and few years, third graders can be unusually clever. What troubles me deeply, however, is that this relative standing among third-grade students doesn’t change much throughout their school years. In fact, research shows that achievement measured in third grade can be used to predict achievement in eleventh grade—eight years later—with 80 percent accuracy or better (Bloom, 1964; Casillas et al., 2012; Grimm, 2008; Siegler et al., 2012). All that seems to change is the relative distance between the highest- and lowest-achieving students in the class: each year that distance becomes greater. As educators, we need to ask ourselves whether this high degree of predictability is an unavoidable characteristic of the educational process, or whether we have other choices. Is such “determinism” in educational outcomes inevitable, or is there something we can do to alter these highly predictable results?

Similarly, in education, our task should be to find ways to respond to students’ learning problems so that learning outcomes become much less predictable.

A number of studies have shown that when students are taught in ways that are appropriate for their needs and when they receive targeted help in overcoming individual learning difficulties, virtually all students learn well.

In essence, mastery learning provides teachers with a way to better individualize and personalize teaching and learning within group-based classroom or online environments.

Carroll believed that time needed is determined by the student’s learning rate for that subject, the quality of the instruction, and the student’s ability to understand the instruction.

My comment: But students cannot think that they can procrastinate and not tackle learning with urgency. And they can’t just think that they can wait out the learning and they will receive less work then. We cannot develop students who are shy of work. I believe a good path to making both of these considerations work is having a couple tracks, like B-level work and A-level work. The higher-level students can tackle the more challenging A-level work after finishing the B-level work while the other students have more time to work on the B-level work. But students should have an incentive to work on A-level work (instead of it just being seen as more work to do) by giving A’s instead of B’s for grades and/or letting them sit on couches/chairs/beanbags while doing additional reading. That is just one possible way to differentiate while making it more than just extra work. And there could be some time towards the end of class in which students have free time away from the students still working to give some incentive to getting work done. When I was a kid in school, my parents would not let me watch tv with them, particularly Monday Night Football, until all of my homework was finished. I didn’t have any incomplete assignments. But students nowadays often do not complete assignments and do not have motivation to work hard with urgency in the classroom. Throughout my education, including the earliest elementary grades, I tackled my work with urgency because I wanted to have as little homework as possible. Parents today often do not have high expectations and accountability that help their kids tackle their schoolwork with urgency and responsibility. So, teachers nowadays are needing to think through how to create better mindsets and incentives for their students. Teachers may be told in some schools (and often in those schools) to teach bell-to-bell. But again, and again this very true phrase rings true: It Takes Two to Tango! The teacher can do his/her job, but the students need to do their job too. And the teacher can lecture bell to bell - but that does not mean that the students are learning bell-to-bell, and good teaching would require students to practice and produce their learning. It’s not just a matter of teaching bell-to-bell. Very often the teachers are doing their job, and they often stress about how to get students uphold their end of their work. So providing some time at the end of class for those who worked hard is worth it if it creates a better mindset in students (Kid Inspired Teacher by John Carlson). (This also works better if distractions are removed during class time like computers, devices, and non-assigned seating with distracting peers.) Of course, context varies for each school, and different policies will be needed for each school.

In other words, Bloom believed that if sufficient time and appropriate instruction were provided, virtually all students could learn well. The challenge for educators was to find practical and efficient ways to accomplish this.

However, if we varied the time provided and adapted the learning experiences to match students’ individual learning needs, Bloom believed we could reduce the variation in student learning outcomes. In other words, if teachers differentiated their instructional activities to provide students with more suitable opportunities to learn and more individualized instruction, then a majority of students in the class, perhaps as many as 95 percent or more, might be expected to learn very well and attain mastery.

My comment: I would also add another “if” … If the student has the motivation, discipline, and will. The teacher can try to help some in this department like providing incentives like the Area of Awesomeness (talked about in Kid Inspired Teacher) and removing distractions within the teacher’s power. But in the end it depends on the student and that student’s family and upbringing.

To attain better results and reduce this variation in student learning, Bloom reasoned that we must increase variation in the teaching. In other words, because students vary in their learning aptitudes and preferences, teachers must diversify and differentiate instruction to better meet students’ individual learning needs. The challenge was to find practical ways to do this within the context of group-based classrooms so that all students learn well.

Bloom believed a far better approach would be for teachers to use their classroom assessments as learning tools, and then to follow those assessments with a feedback and corrective process. In other words, instead of using assessments as evaluation devices that mark the end of learning in each unit, Bloom recommended using them as an integral part of the teaching and learning process to identify what students learned well, diagnose students’ individual learning difficulties (feedback), and then prescribe remediation procedures (correctives). This is precisely what happens when an excellent tutor works with an individual student. The tutor regularly recognizes the student for things that are done well. But if the student makes an error, the tutor first points out the error (feedback) and then follows up with further explanation and clarification (correctives) to ensure the student’s understanding. Similarly, academically successful students typically follow up on the mistakes they make on quizzes and assessments. They ask the teacher about the items or prompts they missed, look up the answers in the textbook or other resources, or rework the problems or tasks so that they don’t repeat those errors.

My comment: This also works for a classroom - IF - there is not a student who is way below the level of the rest of the classroom. If students are much lower in level than the rest of the classroom, then they should receive a modified curriculum (not have the same assignments). Scaffolding and correctives are crutches for the original assignment. They are tweaks. And if the original assignment needs to be seriously scaffolded for a student who is much lower in level, that student would probably benefit much more from just a different assignment. The school could also consider that the student should be in a different class that would be appropriate for his/her level.

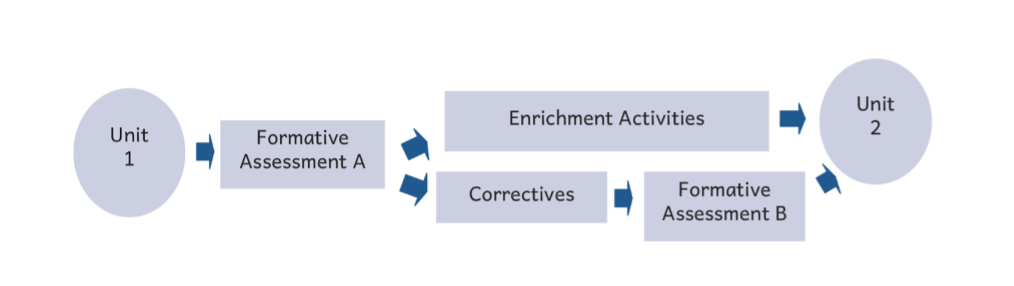

Formative means simply “to inform or to provide information.” A formative assessment identifies for students and teachers precisely what was learned well to that point and where improvements are needed (Bloom, Hastings, et al., 1971; Bloom, Madaus, et al., 1981). Paired with each formative assessment are specific “corrective” activities for students to use in correcting their learning difficulties. Most teachers match these “correctives” to each item, group of items, or set of prompts within the assessment so that students need to work on only those concepts or skills not yet mastered. In this way, the correctives are “individualized” and “personalized.”

Formative “Feedback”

1. Communicates what students are expected to learn

2. Demonstrates what each student has learned well

3. Identifies what each student needs to learn better

- Figure 2.4 illustrates this instructional sequence.

But by recognizing relevant, individual differences among students and then altering instruction to better meet students’ diverse learning needs, Bloom believed the variation among students in how well they learn the specific concepts and skills articulated in a curriculum could eventually reach a “vanishing point” (Bloom, 1971b).

My comment: The teacher is differentiating and breaking students into different learning groups based on formative assessments. But when a class has a wide range of abilities in class with some students just starting school for the first time (SIFEs), the teacher already knows that certain students do not know the material. The teacher already knows the grouping. In these cases, isn’t it best to just have different classes based on ability? Then all students will receive more appropriate instruction for their level and then formative assessments can be used more effectively which tweak instruction. But the formative assessments and tweaking would not be adequate for the massive differences in ability in classes and the need for entirely different curriculums.

Because of its growing popularity, however, mastery learning quickly became a buzzword in education.

My comment: Probably also because schools want to have their cake and eat it too. They want to utilize the most effective system for teaching classes, but they don’t have small class sizes which are needed to make this feasible. The teachers are also burdened with a number of other competing demands which don’t give them the time to implement this system. And this system requires students who can work independently to a degree and who take ownership of their own learning. It works in a classroom without behavior problems and a class in which the teacher doesn’t have to be occupied with classroom management. But in much of American public education the same misbehaving kids keep coming back to the classroom. I see elements of mastery learning in the public school system and in the PDs. But the school ecosystem is not built for its successful implementation. Of course, I think I implemented it better in my ESL 1 class in which I’m completely in charge (in contrast to collab classes).

Programs with fidelity to Bloom’s ideas are built on two essential elements: (1) the feedback, corrective, and enrichment process and (2) instructional alignment

To be effective, this feedback also must be appropriate for students’ level of learning and cognitive development.

My comment: Exactly, the feedback must be appropriate for the student’s level. And if the unit (the starting point) is extremely beyond the student’s level, then the feedback will be beyond the student’s level as well.

To be effective, correctives must be qualitatively different from the initial teaching. Simply having students go back and repeat a process that has already proven unsuccessful is unlikely to yield any better results the second time. Corrective activities, therefore, must provide students with an alternative approach and additional time to learn.

While I recognize the value of this comment and the need for scaffolding for low level students, sometimes students just rush an assignment and/or are careless. And so, they just need to be told to take another look at the problem/assignment before given correctives.

As described earlier, enrichment activities offer students exciting opportunities to broaden and expand their learning. Most important, they provide an incentive for students to prepare for and do well on the first formative assessment. Enrichment activities reward students for their learning success and challenge them to go further.

Some teachers begin by dividing students into separate corrective and enrichment groups immediately after going over the formative assessment. Then they direct students in corrective activities, ensuring that every student who needs extra time and assistance is actively engaged, while the other students work independently on enrichment activities. Other teachers use a team-teaching approach with one teacher leading corrective activities while the other monitors enrichments. After students become accustomed to the process, many teachers incorporate peer-tutoring and small-group study sessions where students work together.

My comment: This requires that students have good class behavior and students can work independently and responsibly. But the American public school system is soft with weak consequences and a lack of accountability (that’s particularly the case for parents of students).

My comment: If one teacher works on correctives while the other works with enrichment, it makes sense to move to different classrooms to minimize distractions and noise conflicts. But the American public schools are so nervous and concentrated on “inclusion” that it is difficult to make this happen. But there is a method called “the piggy-back” method, which I observed in an American school. While studying for my master’s degree and certification in Teaching English as a Second Language, I observed many different classes. A class that used this method was the only collaboration class with beginner level ELs (Newcomers) and native English-speaking students, which a school felt comfortable showing to an outsider. And even with the piggy-back method, it still will require a lot of coordination between co-teachers, including the ESL teacher planning the curriculum with the content teacher at the beginning of the year and for each unit.

In a mastery learning classroom, the pace of the original instruction is determined primarily by the teacher, with sensitivity to the learning backgrounds and characteristics of the students. Support for this idea comes from studies that show younger students in the elementary grades and those with low entry-level skills often lack the self-discipline, motivation, and self-regulation to be good managers of their own learning (Kirschner & van Merriënboer, 2013; Reiser, 1980; Ross & Rakow, 1981). Furthermore, if left on their own to determine the instructional pace, students of all ages frequently suffer “procrastination effects” that can stifle their learning progress.

My comment: Very true. I know of teachers who continually push back due dates and make assignments easier because students are not mastering the standards/TSWs. This is just telling the lazy kids “If you work together in being lazy, you will have less work and more time to goof off.”

Bloom also believed that allowing teachers to determine a sensible and carefully planned instructional pace provided many students with important structure in their learning—especially students who may not be good managers or self-regulators of their own learning (see Linn, 2003). Furthermore, Bloom’s group-based, teacher-paced approach to mastery learning provided a framework for teachers to include of a variety of collaborative learning experiences for students that teachers generally find more difficult to structure in individually paced programs.

In addition, mastery learning principles can be broadly applied. Most educators immediately recognize mastery learning’s usefulness in subjects like mathematics and science. Research shows, however, that mastery learning is equally effective with less-structured subjects like language arts or social studies, especially when instruction focuses on higher-level skills like problem solving, drawing inferences, transferring learning to new contexts, deductive reasoning, or creative writing.

In a writing class, students’ compositions become the formative assessments. Students submit their compositions to the teacher who evaluates the compositions based on the criteria the teacher taught. In some cases, instead of turning in their compositions to the teacher, students exchange compositions with classmates who offer each other individualized, diagnostic feedback based on directions provided by the teacher. Compositions are then returned to the writer with suggestions for revision based upon the specified criteria. Corrective activities then guide students in making revisions, using different techniques than those employed in the initial instruction. Once revisions are completed, students submit their revised compositions to the teacher as the second formative assessment.

Therefore, in analyzing the learning goals and standards for a unit, teachers must consider both the content students are expected to learn and the specific skills they should develop in relation to that content.

A table of specifications provides a brief description of the learning goals and standards to be addressed in a single learning unit, and may be a page or two in length. As we described earlier, the table addresses two basic questions: (1) What should students learn from this unit? and (2) What should students be able to do with what they learn? The first of these questions addresses the content; the second relates to the skills we want students to develop in relation to that content. content. But please note these are both “what” questions. Essential “how” questions related to instruction and assessment—particularly “How will the unit be taught?” and “How will student learning be assessed?”—are not addressed in the table.

Prerequisite preassessments address what students need to know and be able to do in order to start learning a particular unit, either in class or online. Such preassessments typically measure concepts or skills presented in previous grade levels, courses, or lessons.

My comment: And what about those students who are in the class just because of their age, but they do not have any prerequisite knowledge, like Newcomers from Africa and Central America? What’s the point in giving them a pre-assessment when the teacher already knows their level and that they would fail it? Wouldn’t it be better to have classes at their level? That’s much of the point in these teaching practices- providing appropriate instruction and assignments or operating within the zone of proximal development. And these pre-assessments for these low-level students are just a continual reminder that they do not fit in the class - despite loving teachers who do not want the pre-assessment to be seen that way.

Important research evidence shows prerequisite preassessments can be particularly beneficial (Leyton-Soto, 1983; Richland et al., 2009), but only when teachers use results to help students master specific prerequisite knowledge and skills so they are better prepared for upcoming learning tasks. This requires teachers to think carefully about what students need to begin their learning journey, and then to take specific steps to remedy any identified deficits. Using short, informal prerequisite preassessments at the start of learning units, followed by brief reviews, holds promise, especially when students understand the purpose of the preassessment is to ensure their success—not judge or evaluate them as learners.

My comment: And this is when the range in student abilities is not enormous, and the teacher needs a pre-assessment to identify the gaps. When the teacher already knows that some students do not have the pre-requisite knowledge for a course, they should be in a course that is at their level. A student who is learning addition and subtraction should not be put in an Algebra class. The student who is way below the skills needed for algebra will not see the pre-assessment as a way to ensure his success but just a way to judge him and show him that he doesn’t belong there.

In his earliest writings on mastery learning, Benjamin Bloom (1968, 1974) stressed that in every class there are likely to be students who are so bright and so advanced in their learning that special programs need to be designed that challenge them and extend their learning. He thought this may be as many as 5 to 10 percent of students. Bloom also recognized that in every class there are likely to be students whose learning problems and difficulties are so severe that special programs need to be designed for them as well. He estimated this also may be as many as 5 to 10 percent of students. Mastery learning was developed to provide better, more appropriate, and more successful learning experiences for the 80 to 90 percent of students who fall between these two extremes. A preassessment administered at the beginning of a course or instructional series could potentially help identify these exceptional learners so their unique learning needs can be better met. An alternative strategy recommended by Bloom to practically address the diversity in students’ cognitive skills was to increase the pace of instruction in early units and get to the formative assessment process rather quickly. Then, based on the formative assessment results, teachers would use the corrective and enrichment process to provide additional time, to differentiate instruction, and to offer alternative learning activities to accommodate students’ unique learning needs. This would avoid the potentially negative consequences of formal preassessments while providing students with better-targeted and more individualized learning experiences.

At the same time, strong evidence shows the instructional methods of highly effective teachers in any context share two common characteristics. First, their methods originate from a clear and concise vision of what they want students to learn. And second, highly effective teachers have a well-organized plan of how they intend to accomplish that vision.

Highly effective teachers also have clear ideas about what students should be able to do with those key concepts. Rarely are they satisfied with having students simply memorize details or recall factual information. Rather, they want students to be able to use those key concepts, see interrelations, and transfer and apply their understanding to other contexts or new situations. The plans of highly effective teachers generally have two parts. First is a sequence of steps necessary to realize their vision. They identify the learning experiences they believe students should have, the most meaningful order of those experiences (recall Tyler’s second and third questions, described in Chapter 3), the resources necessary to provide those experiences, and procedures for checking on students’ learning progress at regular intervals throughout the instructional process. Excellent teachers align these progress checks to the learning goals or standards they want students to achieve and use them to provide diagnostic and prescriptive prescriptive feedback to students rather than for grading or evaluation purposes. The second part of effective teachers’ plans is a prescribed set of instructional alternatives. Recognizing that no one approach to teaching a particular concept or skill is likely to work well for all students, exemplary teachers consider several ways to present each topic, a variety of examples and illustrations, and different instructional materials and resources. In this way, if one approach falls flat, they have another to which they can immediately turn (Guskey, 1988; Hiebert & Morris, 2012). Having a definite plan with several instructional alternatives prior to teaching allows these teachers to “routinize” large chunks of what goes on in the classroom (Berliner, quoted in Brandt, 1986). Having considered beforehand many of the problems that might arise frees them to respond to situational dilemmas that frequently occur but cannot be anticipated. Finally, highly effective teachers clearly communicate their vision and plan to their students. students. As a result, students see learning not as a “guessing game” where they have to speculate about what the teacher thinks is important, but rather as a well-organized set of learning experiences. Students know from the outset what is expected and what procedures to follow in order to meet those expectations.

Preassessments might also be used as “placement assessments” to ensure the appropriate assignment of students in an instructional sequence or learning trajectory.

My comment: Yes! What I’ve been calling for. Students should be assessed on their skills before moving to the next level/class. Why put a student in algebra if the student has trouble with addition and subtraction, not to mention multiplication and division? And if students are not placed in appropriate classes, then formative assessments lose much of their effectiveness because they are there to tweak instruction on the same level/curriculum. They are not for altering the whole curriculum, which is needed for many students who do not have the requisite skills.

In other words, formative assessments help detect any gaps in understanding. Students can then use that information to improve their learning and teachers can use it to improve the quality of their teaching.

Illustrating the relationships among formative assessment items is especially useful when prescribing corrective activities. For example, a student who doesn’t know the definitions of important terms is unlikely to be able to translate or apply a fact that incorporates those terms. The corrective activity for this student would need to return to the basic definitions of the terms. On the other hand, another student may understand the terms and facts but have difficulty applying that understanding in a new context. This student requires correctives that provide additional practice with transfer and application skills. Including items or prompts that span the range of cognitive skill levels in formative assessments also improves students’ higher-order learning of complex ideas and concepts. Research by Pooja Agarwal (2019, 2020) shows that “mixed” quizzes comprising both fact-based questions and higher-order questions help students develop more sophisticated cognitive retrieval practices and retain what they learned for longer periods of time.

My comment: And these higher ordered questions are made more possible when the content is at the students’ levels. If the student does not understand what is going on in class and does not have the basic building blocks of understanding, then the student cannot build anything with higher ordered thinking because the building blocks just aren’t there.

Regardless of the label, correctives serve a clear and definite purpose in a mastery learning class. They are specifically designed to help correct students’ learning errors and remedy learning problems. Effective corrective activities share four essential characteristics. First, they must initially be conducted in class under the teacher’s direction. Second, they must present the concepts to be learned in a new and different way. Third, they must engage students in learning differently from the initial instruction. And finally, they must provide students with successful learning experiences.

For example, if the teacher’s original instruction involved a verbal explanation with examples, an opportunity to work with manipulative materials might work well as a corrective. If students initially took part in learning groups, an individual task or activity might serve well as a corrective. Whatever the alternative, teachers must ensure students’ engagement is qualitatively different from what it was during the initial instruction.

Any new approach they consider as a corrective will always be their “second best” since they used their “best” in their initial instruction. But when teachers have structured opportunities to plan collaboratively, it’s likely one teacher’s “best” will be different from other teachers’ “best.” Working together, teachers can be excellent resources for each other in planning effective instructional alternatives.

My comment: I would also add that scaffolding as a corrective is qualitatively different. It is a crutch to get to the final product so it is not offered at first to everyone because you want to challenge the whole class and it would ruin the productive struggle for many students.

Like individual tutors, peer and cross-age tutors typically explain concepts from a different perspective than the teacher. Research evidence also indicates that peer and cross-age tutoring is especially effective for students with special needs (Bowman-Perrott et al., 2013; Fulk & King, 2001). In addition, these forms of student-to-student tutoring appear to benefit those who serve as tutors as much as or even more than the students they assist.

Mastery learning teachers who use peer tutoring as a corrective activity typically present it as one of several options students may choose. Compelling students to work together can be counterproductive for both the tutor and the tutee. In addition, students who choose to serve as peer tutors shouldn’t feel compelled to do so in every unit (Hattie, 2006). With each learning unit, students who demonstrate mastery on the formative assessment should have the opportunity to choose from a variety of corrective and enrichment experiences.

With cooperative teams, three to five students get together to discuss their learning problems and to help each other. Teachers typically assign the teams, which stay intact for several learning units. Although no particular grouping strategy needs to be followed in forming these teams, most mastery learning teachers try to ensure the teams are diverse and include students at all skill levels. During correctives, team members review the formative assessment, item by item or point by point. When they encounter a question or important element missed by one or more students, a team member who understands that concept or skill explains it to teammates. If they encounter an item that all team members missed, team members can work together to find a solution or call on the teacher for assistance. After discussing each item and resolving any difficulties, the team moves on to the next item, continuing through the assessment.

My comment: This kind of activity would be a good assignment that is not graded to help students gain competency. But then they should be graded on their individual work after getting prepared with an activity like this. You wouldn’t want to say a student has mastered a TSW when really they just were given the answer by a partner.

Many teachers list textbook page numbers with each item or problem on the formative assessment or on the answer sheet. By carefully reviewing and rereading that portion of the textbook, students often gain a better understanding of the concepts presented. Although referring students to an e-book or print textbook may seem to be “repeating the same old thing” rather than offering a new and different approach, rereading with new focus and intent can be a highly effective corrective. In their initial reading, students have difficulty identifying critical elements or important concepts. Returning to those same passages later with new focus can bring new meaning and better understanding. Early studies of mastery learning programs implemented in high school and college-level classes showed correctives as simple as this can be exceptionally effective in helping students remedy their learning difficulties.

My comment: A scaffolded corrective can be providing the same assignment but with page numbers included. This has the students re-read but also gives them a crutch/scaffold for those who could not do it right initially.

Most mastery learning teachers also correct the formative assessment in class as soon as students have finished. While correcting, they go over each item or assessment criterion, stopping occasionally to reexplain items or concepts that appear to be troublesome to students … At this point, teachers typically divide the class into two groups: students who attained the mastery standard and those who didn’t. Those who achieved mastery move into high-quality enrichment activities or may volunteer to serve as peer tutors. Those who did not begin their corrective work. If the teacher has set up cooperative teams, students simply move together to begin working with their teammates.

In some mastery learning classes, teachers count completed corrective assignments as the “ticket” to the second formative assessment. In other words, to qualify for the second assessment and the “second chance” at success, students must first complete their corrective assignments. These teachers stress that while they are doing special things to help students learn, students have important responsibilities in the process, too—the major one being to complete their correctives.

Enrichment activity: Mastery learning teachers simply pose this challenge to students: “If you wanted your classmates to learn the most important concepts and skills from this unit, how would you teach them?” Students often find coming up with new ways to present particular concepts or introduce new skills to be especially exciting.

My comment: I’m thinking I’ll have the book reading for literacy and cultural studies A-level enrichment, but this could be a good one for science.

In his earliest descriptions of mastery learning, however, Bloom (1976) noted that some students have such severe learning problems that special programs need to be designed for them. He believed this might include the lowest-achieving 5 to 10 percent of students … He developed mastery learning as a way for teachers better meet the learning needs of the 80 to 90 percent of students who fall between these extremes.

This illustrates that there is nothing on summative assessments that students haven’t previously seen in earlier formative experiences where learning difficulties were identified and steps were taken to remedy those difficulties.

To further guarantee students engage in corrective work, most mastery learning teachers have students complete and turn in a written corrective assignment prior to taking formative assessment B.

To achieve these important benefits, about 10 to 20 percent of the items on formative assessments should be spiraling items.

Regardless of their teaching situation, all teachers face challenges in motivating students. Mastery learning helps address many motivation problems by providing teachers with unique opportunities to enhance engagement and improve students’ learning success. Students who experience success in learning enjoy a sense of accomplishment and increased confidence in learning situations. When teachers find ways to help students achieve success in learning and then realize that continued success is within students’ control, motivation problems drastically diminish.

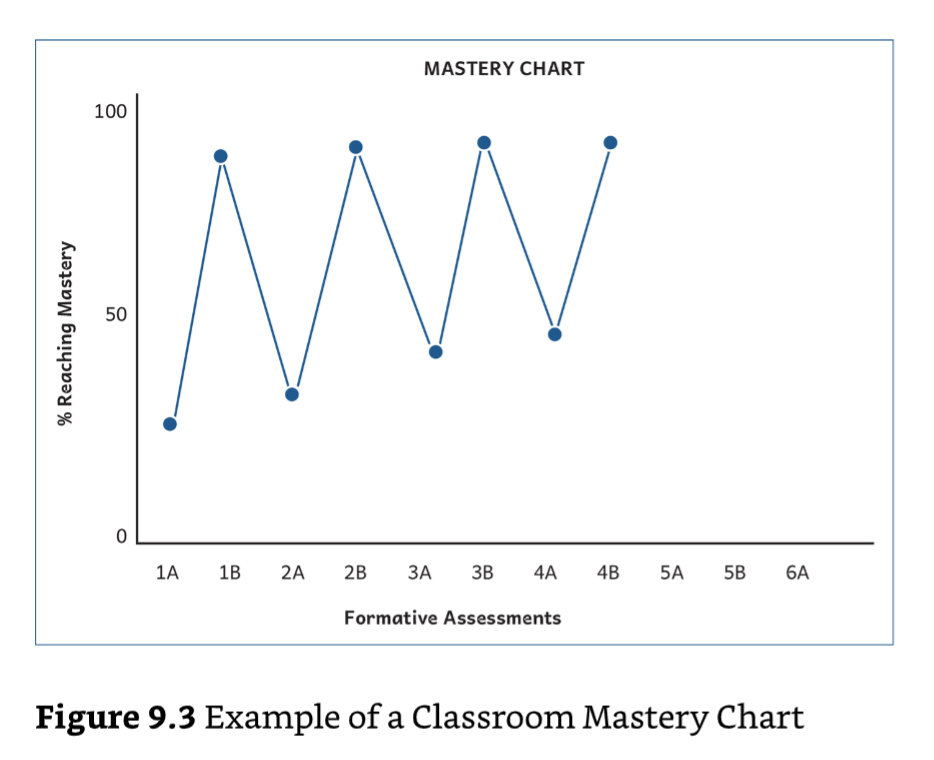

To recognize students’ increased success in mastery learning classes, many teachers post mastery charts in their classrooms, similar to the one illustrated in Figure 9.3. This chart plots the progress of students in the class from unit to unit throughout the term. As the figure shows, only a small percentage of students typically attain mastery on formative assessment A in early units. However, if the planned corrective activities work well, then the majority of students should reach mastery on formative assessment B.

As the term goes on and more students catch on to the mastery learning process, a larger percentage should begin to attain the mastery standard on formative A. This leads to more students being involved in enrichment activities and fewer students taking part in correctives. Furthermore, those involved in corrective work typically have fewer learning errors to correct and can proceed through the corrective phase much more rapidly. A mastery chart like this serves a number of useful purposes. First, it enhances class spirit and encourages collaboration among students. Many teachers find that peer tutoring begins to occur spontaneously in mastery learning classes as students help each other to do well. Some teachers even report that a sense of peer pressure develops where students urge their classmates to do whatever is needed to attain the mastery standard. High school teachers occasionally post a mastery chart such as this for each of their classes and find that competition begins to develop between classes to attain higher mastery percentages. Class mastery charts have many advantages when compared to the typical “progress charts” found in many elementary classrooms that list individual students’ names, followed by colored bars or stars. Charts that list students’ names invite comparison and competition among students, discourage cooperation, and are detrimental to the learning progress of most students. Because mastery charts don’t identify individual students, they encourage student collaboration by depicting progress toward shared learning goals. In addition, mastery charts provide teachers with useful feedback that can help them identify potential trouble spots or implementation problems. For example, the lack of a significant increase in the percentage of students attaining mastery between formative assessments A and B in a unit would be a clear sign of trouble. Perhaps the correctives were ineffective. Maybe students didn’t understand the process or didn’t fully engage in the correctives. Possibly formative B was more difficult than formative A. Whatever the reason, this is a sure sign of problems and a clear indication of the need for change. Likewise, no increase in the percentage of students attaining mastery on formative assessment A from unit to unit would be another sign of problems. Maybe students are not preparing adequately for formative assessment A. Perhaps students don’t find the enrichment activities appealing or rewarding rewarding and feel little incentive to do well. Again, this would be a clear indication that change is needed.